The Swing Riots in Hampshire.

The Swing Riots of 1830 were an uprising by agricultural workers in parts of Eastern and Southern England. It was a civil unrest that was a long time in the making, the stirrings of unrest began in the 1780’s and then during the Napoleonic Wars faded away somewhat. Fifty years later the agricultural poor could suffer no more and rebellion was born in the guise of the Swing Riots. Hampshire agricultural workers were in the thick of it and when the time of reckoning came many found themselves before the courts to face harsh sentences.

Some background to the Swing Riots.

Many factors contributed to the Swing Riots, it was a complex set of circumstances that brought things to a head in 1830.

Between 1770 and 1830 about six million acres of common land in England was enclosed. This common land had been used for hundreds of years by the poor to graze cattle and plant produce. It was a vital part of life for the poor of Britain, there was no such class as landed smallholding peasantry so when the common lands were enclosed and the peasants rights removed, they were thrown into a state of subservient destitution.

The land was divided up amongst the large landowners, forcing people to be solely dependent upon working for the rich landowners for money to buy the food they used to raise by their own toil.

However other things were happening that were affecting the landless poor. In the 1780’s the hiring fair was where agricultural workers went to secure a year long contract from farmers and landowners. This year long contract bought security for the agricultural workers, peace of mind and food in his farmer’s larder. Landowners however were feeling the squeeze of poor harvests and started to only offer short contracts of work, a week or months worth instead. The strain this placed on the poor agricultural worker was enormous and an unsettled, disgruntled workforce began to emerge.

None of these factors alone alone precipitated the riots. Britain had been at war with France from 1803 – 1815. The Napoleonic War, although a disturbing and frightening period did at least boost the wages of the agricultural workers. Labour was in short supply and corn prices were high. For once workers were able to earn a fair living.

However when peace broke out in 1815 and the military were disbanded in the southern ports, they moved inland looking for work. There simply were not enough jobs to go around, the oversupply of labour caused wages to fall and unemployment rose and rose. At the same time grain prices that had held their price began to plummet. Britain faced one of its darkest periods.

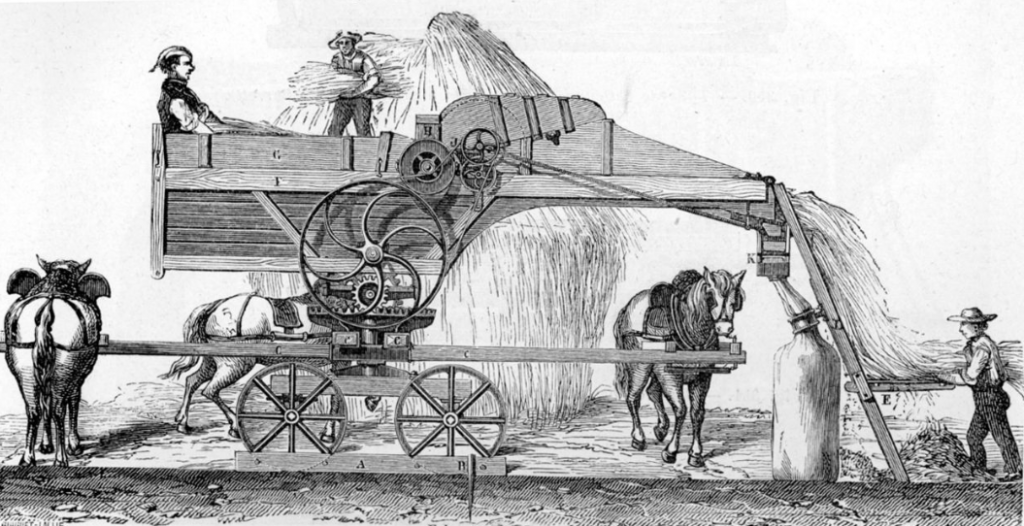

Finally the emergence of mechanised farm machinery, in particular the threshing machines, brought the agricultural worker to break the rules. They were joined in Hampshire by a group of well educated radical men who were followers of William Cobbett. Hampshire was one of the southern counties most severely affected by the protest and the judiciary determined to put the riots down with was the first to experience the systematic, chillingly deliberate judicial terror by which protest was repressed.

The Riots Unfold.

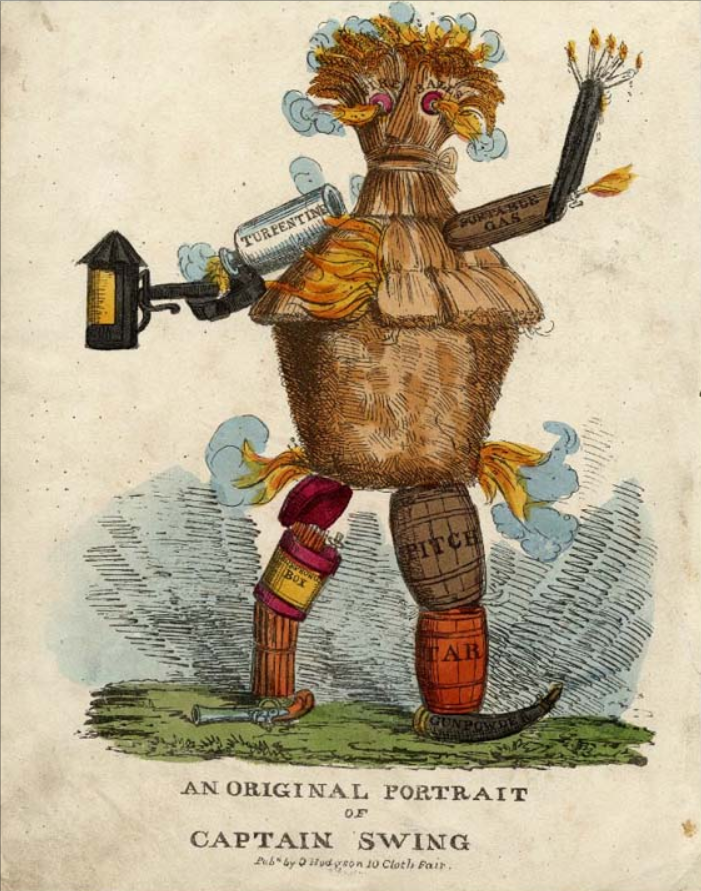

In 1830 letters were received by Hampshire farmers and landowners signed by ‘Captain Swing’ stating that if their threshing machines were not destroyed then ‘on behalf of whole we will commence our labours’.

Captain Swing was a made-up name representing the anger of the labourers in rural England who wanted a change in their circumstances, the right to contracted labour, fair wages and no machines. These threatening letters first appeared in Kent and West Sussex and then spread to Hampshire and Wiltshire.

The riots in Hampshire seemed to be particularly aggressive and there was an added element of the intelligentsia. William Cobbett that relentless reforming campaigner, pamphleteer, farmer, journalist and member of parliament, wrote about the appalling condition of the agricultural labourers as he journeyed through England including Hampshire in his narrative ‘Rural Rides’. He campaigned for the abolishment of “rotten boroughs”, thinking this would ease the poverty of farm labourers. Many agreed with him but wanted a more radical approach that would take the fight directly to the landowners.

It was probably because of this that the riots took on a more serious tone in Hampshire and subsequently the rioters were dealt with more severely in Hampshire compared with elsewhere. The Duke of Wellington was the Lord Lieutenant of Hampshire and he was determined that any riots should be completely crushed.

November 1830, the Swing Riots erupt in Hampshire.

Although the Swing Riots occurred in pockets all over the county there was a particular focus of rioting in the area of the Dever Valley and in the Andover area.

The cold dark days of November when many agricultural workers would be working shorter days as Winter started to bite. Cold homes, emptier larders may just have been the tipping point for the aggrieved workers.

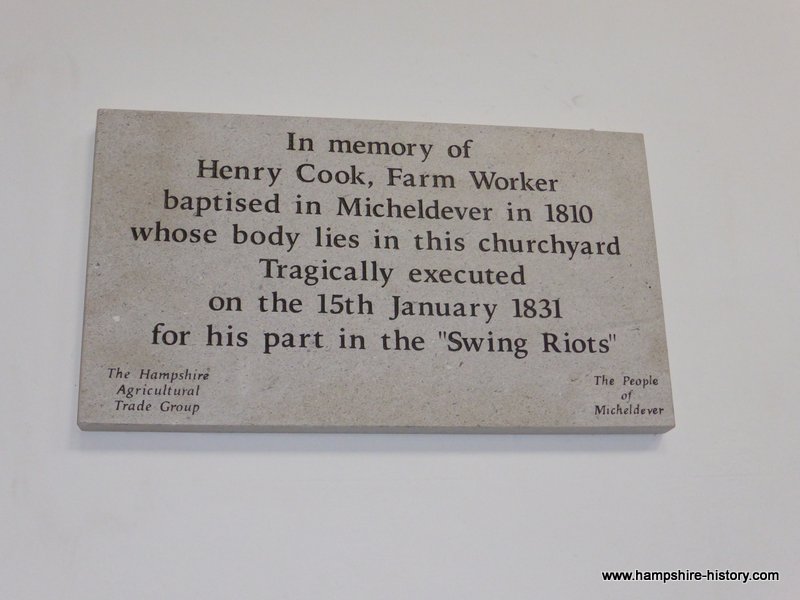

Gangs of labourers started to roam the villages, at Barton Stacey money was demanded from the curate before three barns were destroyed, the barns may have been storing machinery. Seven hundred labourers from around Micheldever destroyed all the threshing machinery they could find. Others marched to The Grange at Northington, then owned by the Baring family and a violent confrontation took place resulting in a hammer blow being aimed at one William Barry. It glanced off his head and knocked his hat off. A lad called Henry Cook offered up the blow and he was arrested and charged with attempted murder. Troops were summoned from Portsmouth to restore order.

At Andover the riots lasted several days and on the 20th November 1830 a mob descended upon Taskers Waterloo Ironworks at Upper Clatford and destroyed all the machinery they could. Robert Tasker who owned the works and employed many men from the surrounding area was sympathetic to their cause, he refused to identify any of those involved but those who were rounded up were sentenced to transportation.

On Sunday the 21st November, the Sabbath day, when many would have been home, the mob went from house to inn demanding food and money. They trawled their way through Houghton Mill, Bossington House, the Kings Arms at Stockbridge and Rookley House at Kings Somborne.

On Monday the 22nd November the mob targeted the workhouses at Selborne and Headley and did a great deal of damage. They only stopped when the vicar agreed to reduce the tithe payment by half. The Selborne mob were summoned by a horn, blown by John Newland (the trumpeter). He escaped up into the Selborne Hangar but was captured six months later and sentenced to hard labour.

Meetings between the mob and the magistrates take place.

Dr Quarrier,John Coles both magistrates and Bonham Carter High Sherriff, took it into their hands to intervene to prevent a gathering of the labourers at Steep Church yard. They asked the farmers not to allow their labourers to attend the meeting though quite how they would have achieved this is difficult to understand however they managed to prevent the Steep meeting and another that was arranged to be held in the market square at Petersfield from taking place.

Quelling the Swing Riots.

Lord Melbourne was Home Secretary at the time and although he aimed for a balanced response felt that there was too much sympathy being shown towards the rioters and he blamed the escalation and continuance of the riots upon too lenient magistrates. There is no doubt that these riots scared farmers and landowners. Looking back at Revolution in France it is easy to see why.

Melbourne took matters into his own hands and appointed a Special Commission of judges to try the rioters and they were dealt with harshly. Many were condemned to death (about 252) but only 19 were hanged. 644 were imprisoned and 48 were transported. At this point it is worth saying that those brought to trial were not just agricultural workers, blacksmiths, cobblers, carpenters and many other artisans were also involved, hence the concern that what was being witnessed was a grass roots revolution.

William Cobbett.

William Cobbett was held up as being responsible for stirring up the rural poor especially in Hampshire. His article the ‘Rural War’ examined the Swing Riots and lay the blame with those who lived off unearned income at the expense of the rural poor and he urged parliamentary reform. He was charged with seditious libel but attacked the prosecution and was acquitted.

Hampshire names and the Swing Riots.

There are many places to find the names of those charged, a trawl through the Quarter Sessions books at Winchester Archive is a good place to start and we are adding them to the table of Hampshire names with a few brief notes so if you have Hampshire family connections pop your surnames into the table and see if one of your ancestors was involved.

Places in Hampshire where rioting took place.

Wickham, Littleton, Owslebury, Penton Grafton, Stockbridge, Barton Stacey, Vernham’s Dean, Highclere, Burghclere, Fordingbridge, Basingstoke, Wootton St Lawrence, Monk Sherborne, Leckford, Romsey, East Woodhay, Mitcheldever, Stratton, Upper Clatford, Selborne, Headley, Andover, Itchen Abbas, Martyr Worthy, New Alresford, Thruxton, Fawley, Houghton, Droxford, Upham, Mottisfont, Bighton, Exbury, Durley, South Stoneham, Corhampton, Warblington, Bossington, Havant, Crawley, Broughton, Farringdon, Upper Wallop, Binsted, Buriton, Bishops Waltham, Kimpton, Kingsley, Greatham, Enham, Weyhill, East Wellow, Northington, St Mary Bourne, Rockbourne, East Tytherley, Leckford.